I’ve always been a bit precious about gift-giving, haven’t I? If you’ve read any of my other pieces, you know I’m the sort who keeps detailed notes on preferences, maintains color-coded spreadsheets of past presents, and generally approaches the whole business with the strategic intensity of someone planning a military campaign rather than selecting a birthday present.

For years, I operated as a gift-giving lone wolf. When family suggested going in together on presents, I’d smile politely while internally thinking, “No thanks, I work alone.” The very idea of collaborative gift selection seemed like a compromise at best, a recipe for mediocrity at worst. After all, wouldn’t combining ideas inevitably lead to watered-down concepts, design-by-committee presents that lacked the personal touch?

Oh, how gloriously wrong I was.

My conversion to cooperative gift-giving happened entirely by accident four years ago, courtesy of my brother Tom’s 40th birthday. I’d been planning an elaborate gift for months—a custom-built record storage unit for his growing vinyl collection, designed to fit perfectly in the awkward alcove of his living room. I’d consulted with a carpenter, selected the wood, and was just about to place the order when our mother called.

“I’ve had a brilliant idea for Tom’s birthday,” she announced. “What about a proper record storage cabinet for all those albums he keeps stacked on the floor? I’ve even found someone who could build it.”

I nearly dropped the phone. She’d landed on exactly the same idea, right down to having found the same local carpenter. My first reaction was territorial annoyance—this was MY gift idea, thank you very much! But as she enthusiastically described her vision, I realized it was both remarkably similar to mine and different in intriguing ways. She’d thought about interior dividers I hadn’t considered. I’d planned a finish that would better match his existing furniture.

“Actually,” I heard myself saying, “what if we did this together? Combined our budgets and ideas?”

What followed was a revelation. Through several conversations and shared Pinterest boards (yes, my 68-year-old mother uses Pinterest, and with surprising skill), we created a design far superior to what either of us had initially envisioned. Mum thought about practical elements I’d overlooked in my aesthetic focus. I pushed for design details that elevated it from purely functional to genuinely special. The carpenter, relieved to have consolidated client input, incorporated our collective vision into something that exceeded both our original concepts.

When Tom unwrapped a miniature model of the cabinet (the actual piece being too large to wrap), along with photos of the in-progress build, his reaction was unlike anything I’d seen from previous solo-mission gifts. “This is incredible,” he kept saying, examining every detail of the design. “It’s exactly what I needed but so much better than I would have thought to ask for.”

The cabinet has become the centerpiece of his living room, regularly photographed by vinyl-enthusiast friends for their own inspiration. It remains one of the most successful gifts I’ve ever been involved with—not despite the collaboration but because of it.

That experience cracked open something fundamental in my approach to giving. I’d been so focused on the personal triumph of finding the “perfect” gift that I’d missed the multiplicative power of collaborative creativity. When gift-givers combine their different perspectives, resources, and insights about the recipient, the result can transcend what any individual could achieve alone.

Since that revelation with Tom’s cabinet, I’ve become a proper evangelist for cooperative gift-giving. I’ve organized gift collaborations for significant birthdays, wedding presents, new baby celebrations, and milestone anniversaries. With each project, I’ve refined my understanding of when and how collective giving works best.

Take my friend Priya’s wedding gift, for instance. When she and her partner announced their engagement, several of us from university wanted to get them something special. Individually, we were each considering variations on kitchen equipment, tableware, or home décor—all lovely but somewhat expected.

Over coffee one afternoon, we started casually discussing our ideas, and a much more compelling possibility emerged. We realized that collectively, our friend group contained a photographer, a writer, a graphic designer, and me (the obsessive gift planner). What if, instead of physical objects, we created something that utilized all our skills?

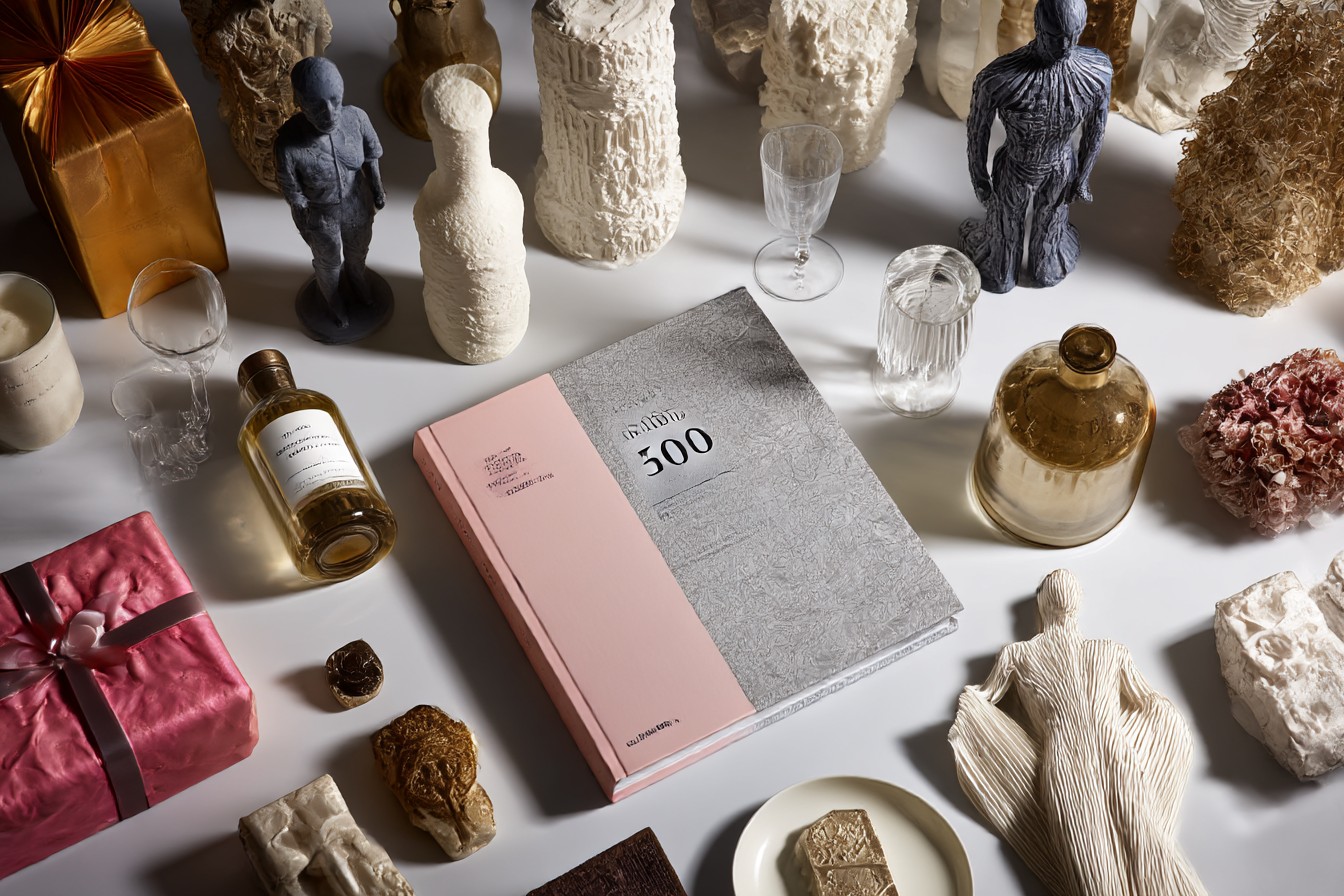

The result was a completely bespoke commemorative book documenting Priya and her partner’s relationship. Our photographer friend conducted a proper photo shoot of the couple in significant locations from their relationship. The writer interviewed their family members and friends, collecting stories and memories. The graphic designer created a stunning layout incorporating these elements along with scanned mementos like ticket stubs and handwritten notes I’d helped collect from their families.

The final product—professionally printed and bound in small-batch production—was something none of us could have created individually, either financially or in terms of skills. It combined professional-quality elements that would have cost thousands to commission, all made possible through our collaborative effort.

When they opened it at their wedding reception, Priya was speechless for a full minute before bursting into tears. “This is us,” she kept saying, turning the pages slowly. “This is actually us.” Four years later, that book still sits prominently on their coffee table, regularly shown to visitors and, according to Priya, “the one thing I’d grab in a fire after the cats.”

What makes cooperative gift-giving so powerful isn’t just the practical pooling of financial resources (though that certainly helps for more ambitious presents). It’s the diversity of perspectives and skills that creates true gift alchemy.

When my colleague Olivia had her first baby after a difficult journey through fertility treatments, our work team wanted to give her something meaningful. Individually, we were all contemplating the usual new baby gifts—clothes, toys, practical items. Nice, but hardly memorable among the flood of similar presents she’d receive.

During a lunch discussion, our collective knowledge of Olivia revealed something important: she’d always been passionate about nature and had mentioned wanting to create a “backyard wildlife sanctuary” at their new home but expected that dream to be delayed indefinitely with a newborn.

What if, we realized, we could make that happen for her?

Our collaborative approach allowed for someone to research native plants suitable for wildlife attraction in her specific area. Another colleague with gardening experience selected species that would require minimal maintenance. Someone else created a planting design that could be implemented in phases as the baby grew. I coordinated with a local nursery that could deliver and plant everything according to our plan.

The gift—presented as a beautiful illustrated plan with the first phase of plants already scheduled for delivery and planting—reduced Olivia to happy tears. “You’ve given me back something I thought I’d have to give up,” she told us. “The baby and I will watch this grow together.”

Over the following year, we heard regular updates about fox cubs playing in the meadow area we’d helped establish, the first butterflies on the lavender, and how sitting by the window watching birds at the feeders became a special bonding time during late-night feeding sessions with her daughter. The cooperative nature of our gift had created something far more meaningful than any individual present could have been.

I’ve found that certain occasions particularly benefit from cooperative approaches. Milestone birthdays—40ths, 50ths, 60ths—often call for something more significant than everyday presents. Wedding gifts provide natural opportunities for collective giving, allowing for presents of greater impact than typical registry items. And “difficult to buy for” recipients—those who seemingly have everything—frequently yield to collective creativity when individual ideas fall short.

My father-in-law, notoriously impossible to shop for, had resisted all conventional gift attempts for years. “Don’t waste your money,” he’d say every birthday and Christmas. “I don’t need anything.” Individual family members had resigned themselves to token presents that generated polite but unenthusiastic responses.

For his 70th birthday, I suggested a family collaboration. Through careful conversations with different relatives, a pattern emerged: he frequently reminisced about the small Yorkshire village where he’d grown up but hadn’t visited in over twenty years. Various obstacles—his wife’s mobility issues, the distance from their current home, the emotional weight of returning to a much-changed place—had made it seem complicated.

Our collective gift became a carefully planned long weekend return to his hometown, with every potential obstacle addressed through our combined knowledge and resources. My brother-in-law researched accessible accommodation options. Charlie’s sister, who lives nearest to the village, scoped out which childhood landmarks still existed. I created a custom guidebook with then-and-now photos sourced from local historical societies and family albums. His grandchildren recorded video interviews with still-local residents who remembered his family.

When he unwrapped the beautifully presented trip plan, complete with train tickets and the supporting materials we’d created, his usual polite restraint crumbled completely. “You’ve thought of everything,” he said quietly, voice thick with emotion. “I never thought I’d go back.”

That trip became a pivotal family experience, yielding stories he’d never previously shared and creating new memories alongside revisited ones. No individual gift-giver could have created such a comprehensive experience, addressing both practical needs and emotional nuances. It required our collective insight, resources, and implementation.

Of course, cooperative gift-giving isn’t without its challenges. Different contributors may have varying budgets, potentially creating awkward dynamics. Conflicting aesthetic judgments can lead to compromise designs that please no one entirely. And strong personalities (I reluctantly include myself in this category) sometimes struggle to relinquish control over the final outcome.

Over years of collaborative projects, I’ve developed some practical approaches to maximize the benefits while minimizing the friction:

Clear but flexible leadership helps tremendously. Most successful group gifts have someone serving as primary coordinator (a role I often volunteer for, shocking no one who knows me). This person keeps track of the timeline, consolidates input, and ensures forward momentum, while still respecting the collaborative nature of the process.

For my grandmother’s 90th birthday, I created a shared digital workspace where family members could contribute ideas, vote on options, and track our progress. As coordinator, I set deadlines, summarized discussions, and moved decisions forward when they threatened to stall in endless debate over details. The result—a beautifully curated memory box with contributions from four generations of family members—required both collective input and structured management.

Defining contribution expectations early prevents resentment. Some collaborative gifts involve equal financial contributions, while others work better with varying financial inputs balanced by different forms of effort. Being explicit about these expectations from the outset avoids uncomfortable situations later.

When organizing a group gift for a retiring colleague, I created a sliding scale of suggested contributions based on seniority and relationship closeness, while also offering “effort alternatives” for those with limited finances but valuable skills or time to offer. This transparent approach allowed everyone to participate meaningfully without financial stress.

Focusing on complementary strengths rather than compromise designs typically yields better results. Instead of having everyone weigh in equally on every aspect, identify what each contributor does best and create space for those strengths to shine.

For my friend James’s 40th birthday adventure gift, one friend with travel industry connections secured special experiences. Another with detailed knowledge of James’s food preferences planned the meals. Someone else with graphic design skills created the presentation materials. I handled the overall logistics and timeline. Rather than averaging out our ideas, we each owned different aspects of the project.

Documentation and communication tools make a tremendous difference. Shared Pinterest boards, collaborative documents, group messaging, and project management apps have all proven invaluable for keeping everyone engaged and informed without endless email chains or meeting fatigue.

For planning my parents’ anniversary celebration, we created a shared digital folder where scattered family members could contribute photos, memories, and ideas asynchronously across multiple time zones. This approach allowed my brother in Australia to be as involved as those of us in the UK, resulting in a truly family-wide collaboration despite geographic challenges.

Perhaps most importantly, I’ve learned that the best collaborative gifts maintain a singular focus on the recipient’s joy rather than any contributor’s vision. When disputes arise—as they inevitably do—returning to the central question “What would most delight this specific person?” usually clarifies the path forward.

When debating elements of a group-funded garden renovation for our friend Sonia, opinions diverged about aesthetic choices. Redirecting the conversation to what would best suit Sonia’s specific preferences and needs—rather than anyone’s personal garden ideals—quickly resolved the impasse and refocused our collective energy.

The results of these collaborative approaches have consistently exceeded what I could have achieved alone, both in scope and in emotional impact. There’s something uniquely powerful about receiving a gift that represents the combined insight, effort, and care of multiple people who value you.

My mother’s 70th birthday present—a collaborative recipe collection gathering family dishes across generations and continents—brought together contributions from relatives who rarely communicate directly. The final collection included not just recipes but stories, memories, and photographs spanning our extended family history. As she paged through it for the first time, she kept saying, “Everyone did this? Together? For me?” The collective nature of the gift carried as much emotional weight as its content.

This shift toward cooperative gift-giving has changed not just how I approach presents but how I view relationships more broadly. I’ve watched family members who typically interact superficially engage in meaningful conversations about shared memories while planning collaborative gifts. I’ve seen friendships deepen through the vulnerability of creative collaboration. I’ve witnessed the healing of old tensions when focused on a common goal of bringing joy to someone mutual beloved.

The process itself often becomes its own form of gift—not just to the recipient but to everyone involved. Working together on something meaningful creates connection and shared purpose that extends beyond the present itself. Some of my closest current friendships have been strengthened through successful gift collaborations, the shared achievement creating bonds that transcend the initial project.

I still maintain my color-coded spreadsheets and meticulous preference notes. I still occasionally execute solo gift missions for everyday occasions. But for the truly significant moments—the milestone celebrations, the once-in-a-lifetime opportunities, the difficult-to-delight recipients—I now instinctively reach out to potential collaborators rather than going it alone.

Because what I’ve discovered, somewhat to my perfectionistic surprise, is that the most perfect gifts often emerge not from individual brilliance but from collective care—from the magic that happens when different perspectives, skills, and insights combine in service of bringing joy to someone all contributors value.

So the next time you’re facing a significant gift occasion, consider who else might want to join forces with you. Who brings complementary knowledge about the recipient? Who offers skills or resources different from your own? Who shares your desire to create something truly meaningful?

You might just find, as I have, that the gift-giving lone wolf approach—satisfying as it can sometimes be—pales in comparison to the creativity, impact, and connection that emerges when we give cooperatively. Some things really are better together than apart. And truly special gifts, it turns out, are absolutely among them.